BOOKS

TWOSOMES

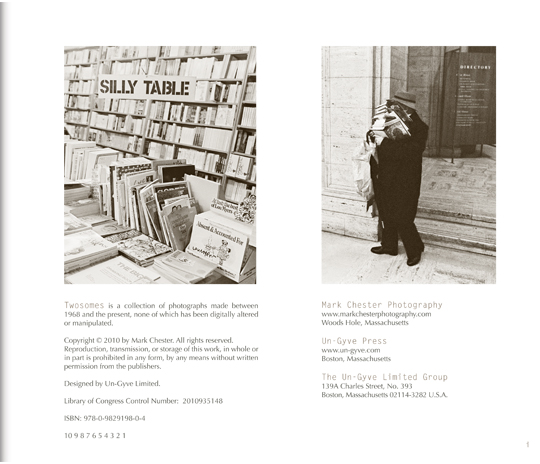

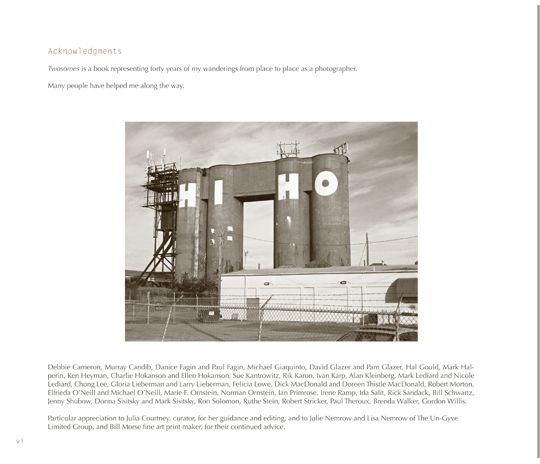

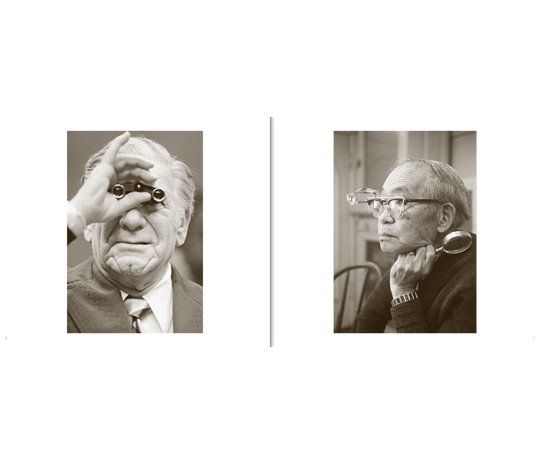

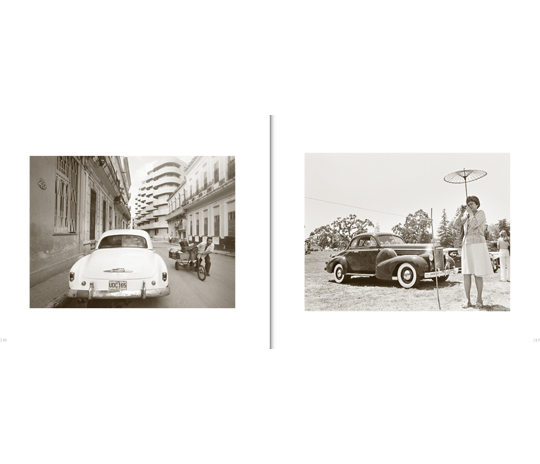

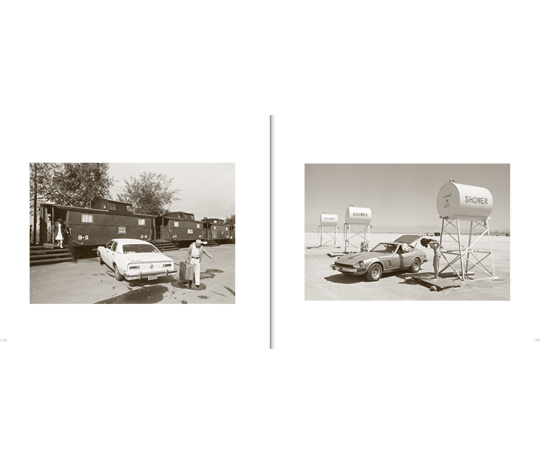

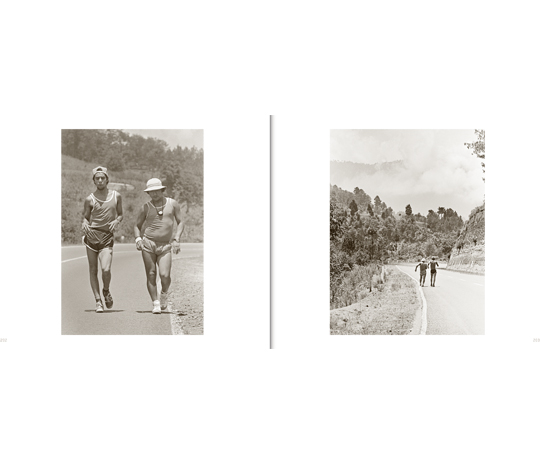

Published in 2011 by Un-Gyve Press the 218 page hardcover book Twosomes features 202 plates, 101 image pairs representing forty years of photography by Mark Chester.

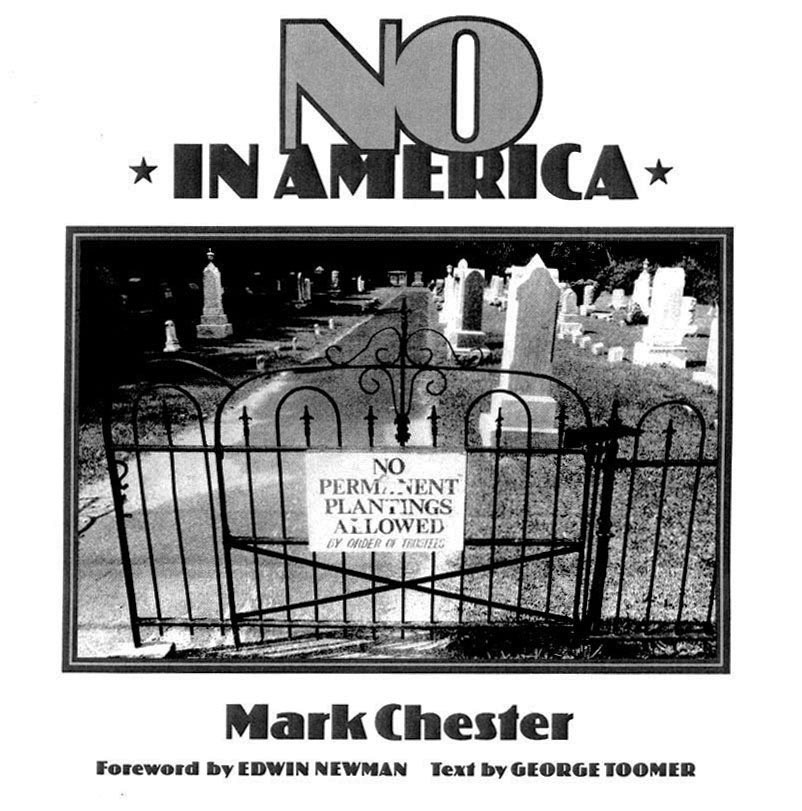

NO IN AMERICA

Published in 1986 as a signed limited edition hardcover book of five-hundred copies, as well as a softcover, Mark Chester's No in America is a collection of photographs documenting the word as it occurs on public notices, official and handmade, with text by George Toomer and a foreword by Edwin Newman.

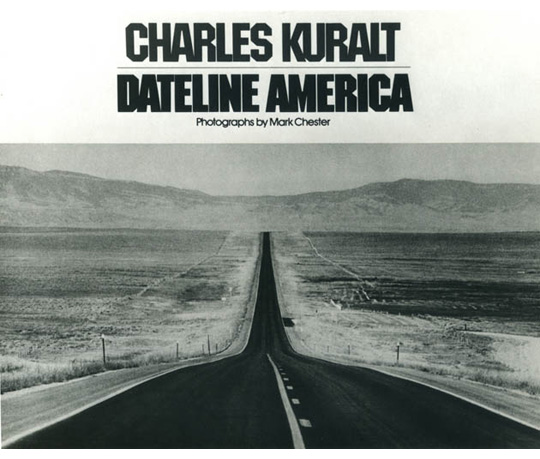

DATELINE AMERICA

Published in 1979 by Harcourt Brace Jovanovich Charles Kuralt's Dateline America book of essays is accompanied by Mark Chester's photographs.

2011 - 2015

The ethnic diversity series is photographed in Massachusetts, portraits of naturalized citizens from nearly 170 countries residing in the state for the publication of The Bay State: A Multicultural Landscape.

Twosomes is a 2012 PDN Photo Annual winner in the Book Category.

JUNE 2011

Twosomes book release June 2, 2011 from Un-Gyve Press. Launch at the Brookline Booksmith on June 6. Touring exhibition opens on June 18 at The Cape Cod Museum of Art.

1987

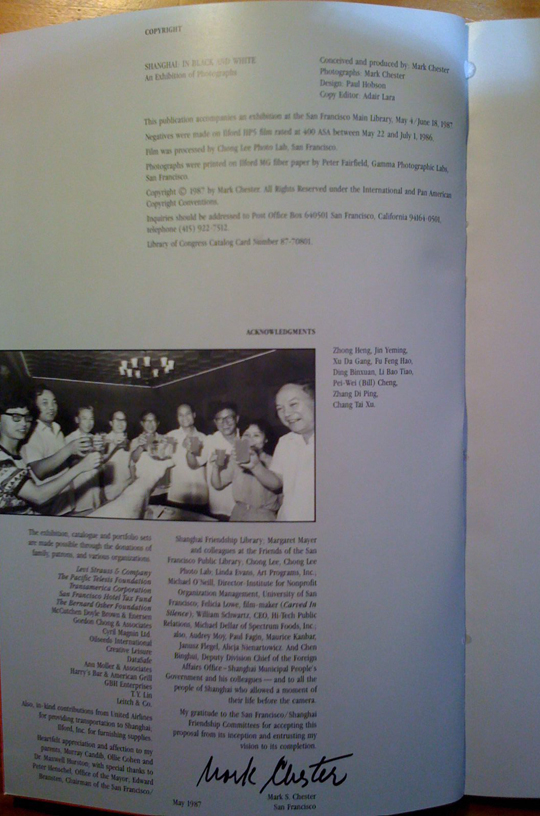

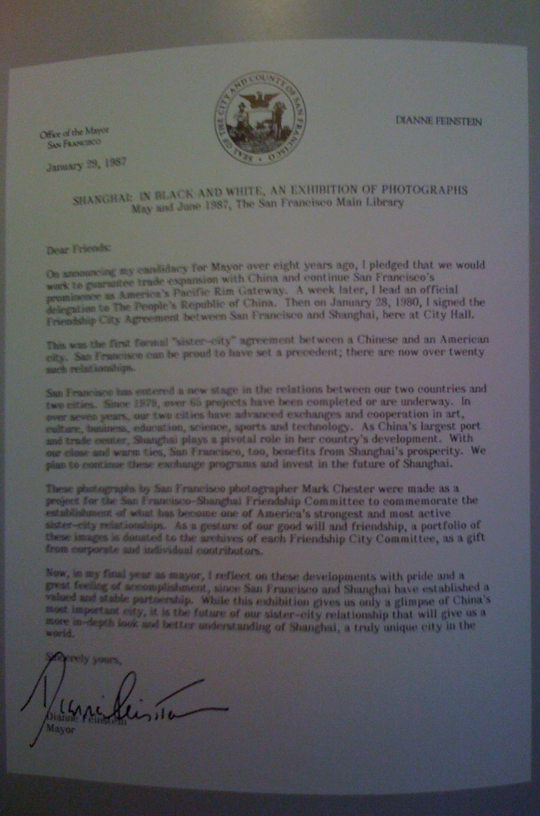

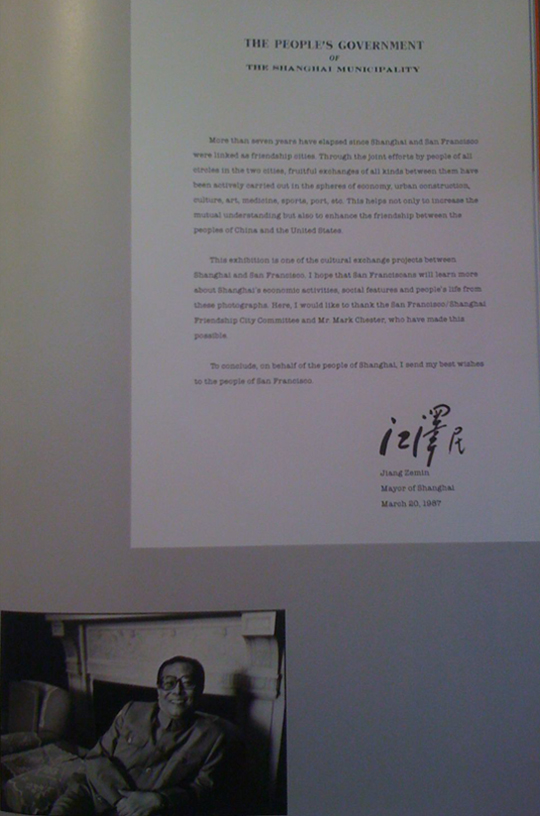

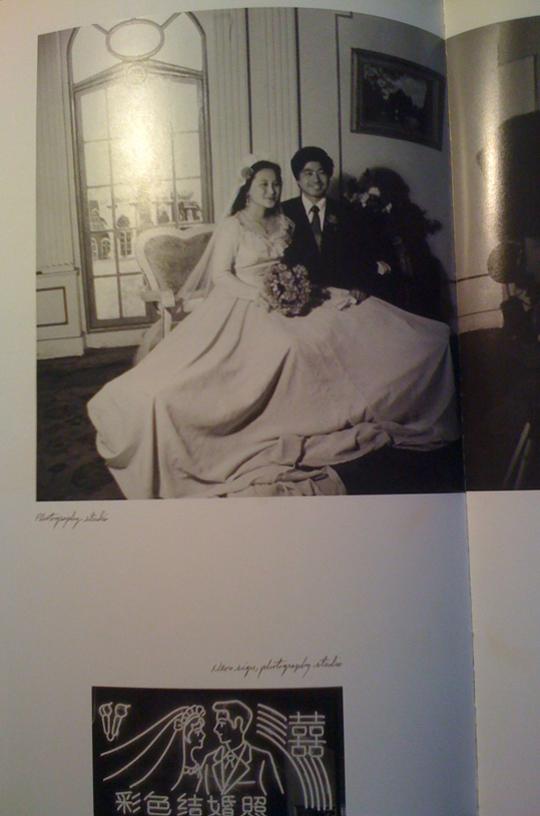

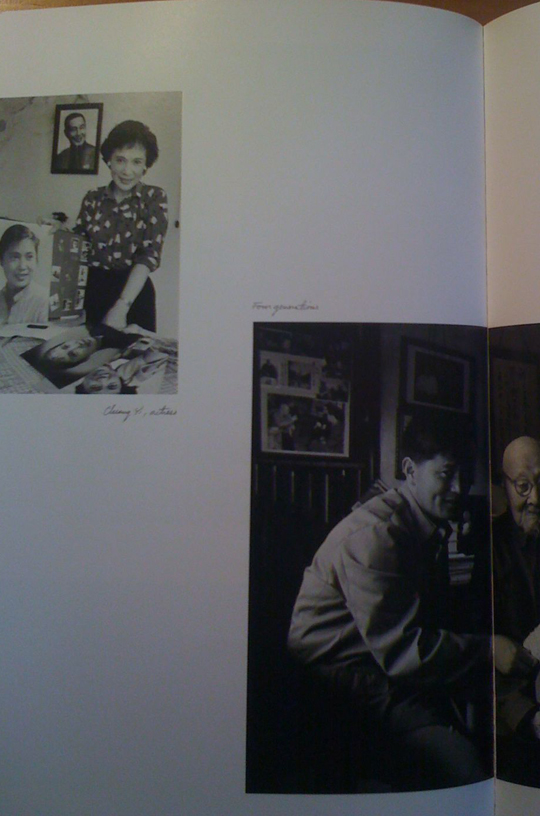

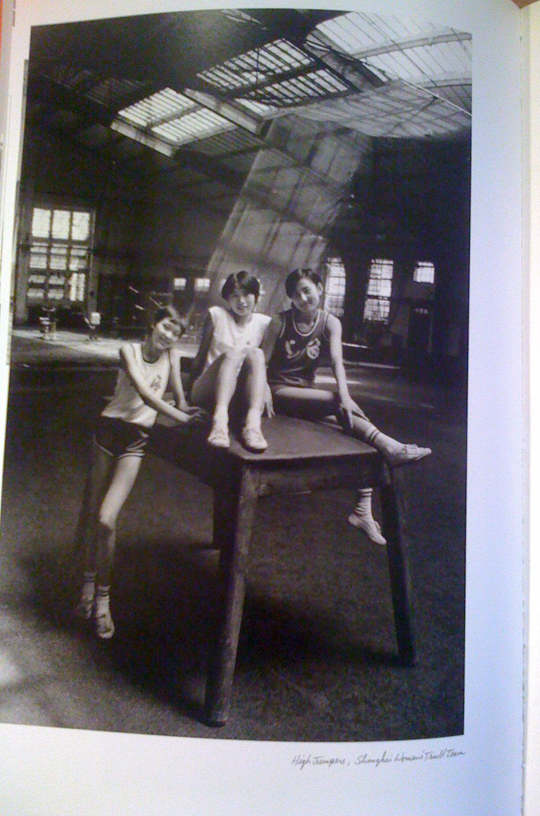

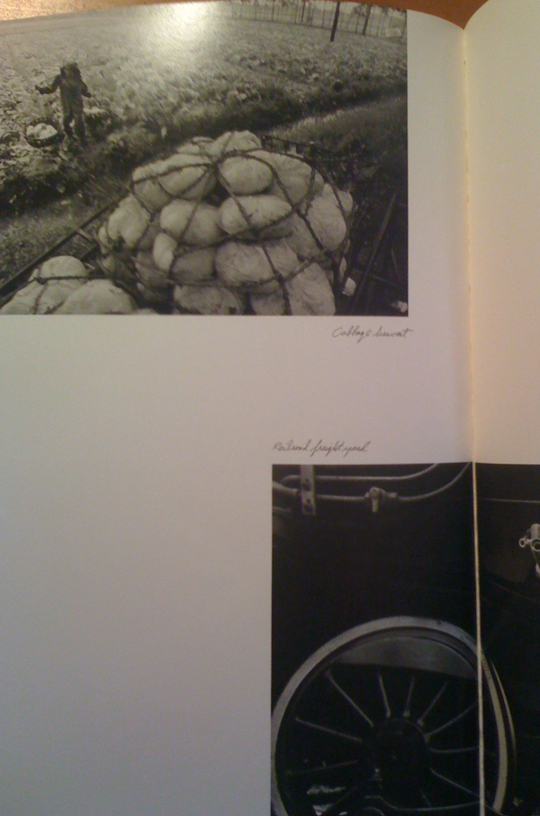

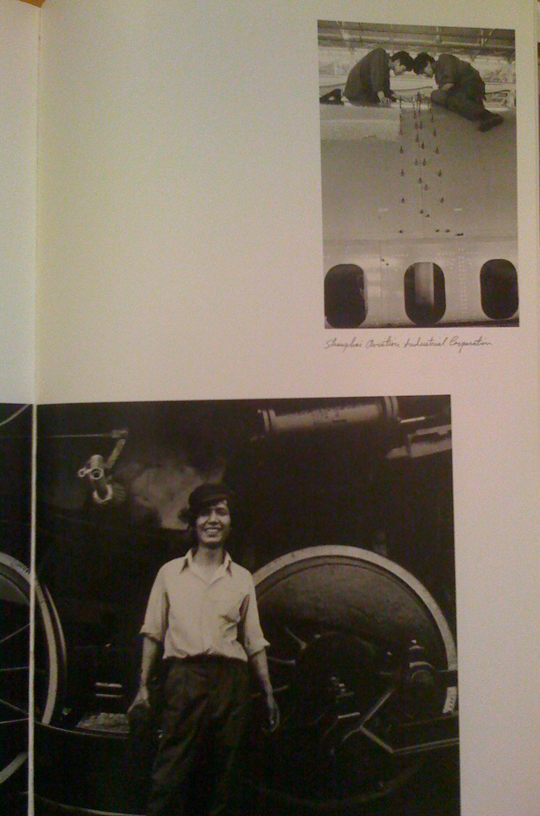

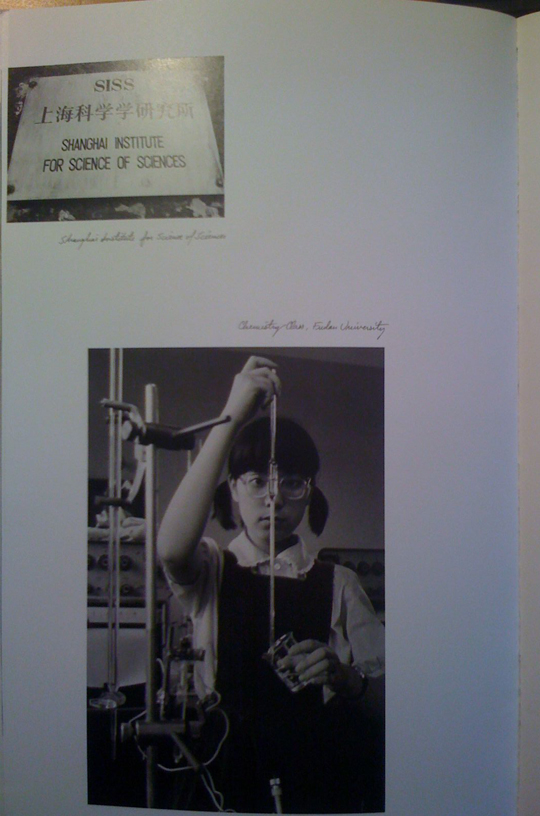

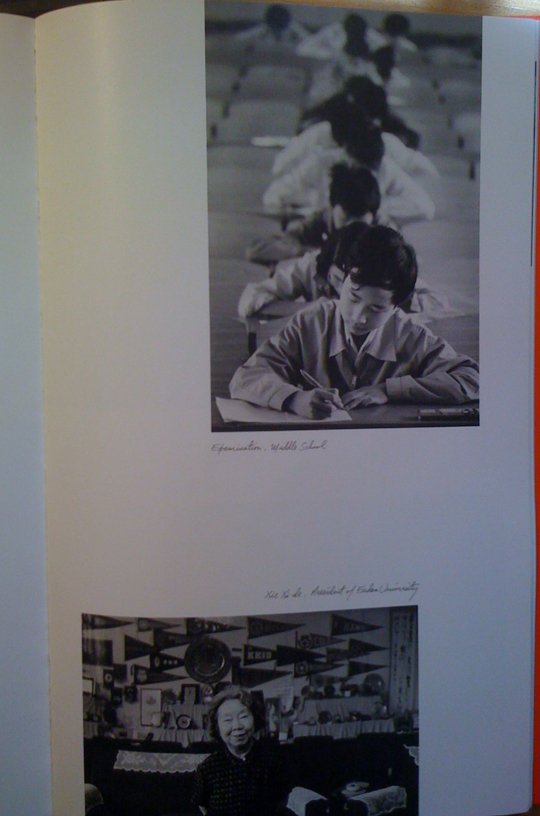

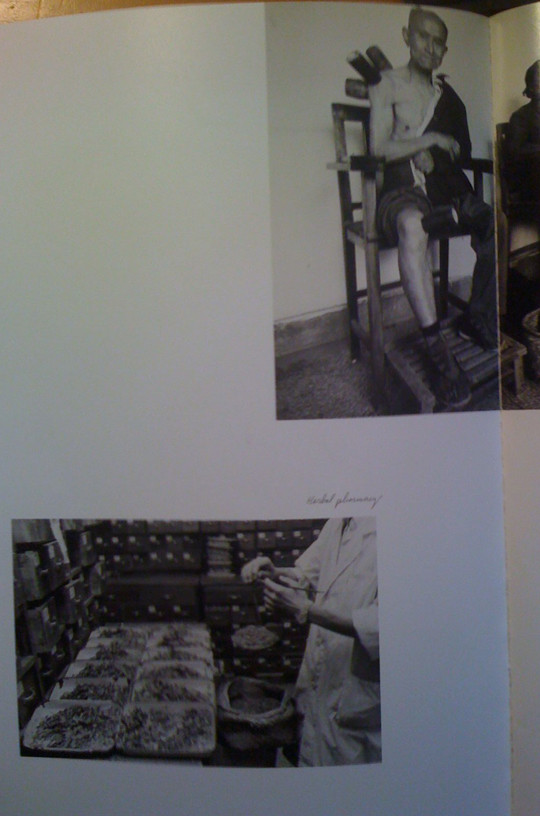

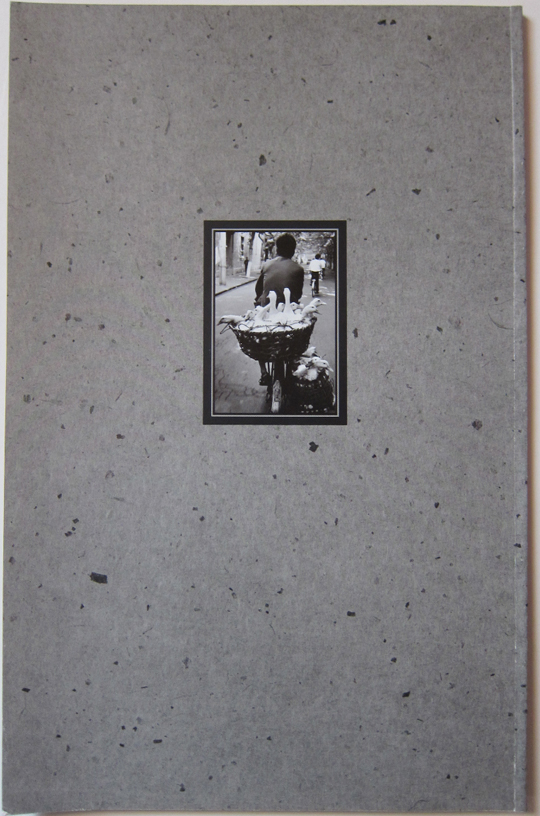

In 1987, Mark Chester created and produced the traveling exhibition and catalog, Shanghai: In Black and White, in commemoration of San Francisco's Sister City as part of a cultural exchange program. The photographs were displayed at the Fort Lauderdale, FL, Museum of Art; The Sidwell Friends School, Washington, DC; and the San Francisco Main Library.

SEPTEMBER 1986

No In America

1983

Sumo series photographed in Nagoya, Japan.

JUNE 1979

Dateline America

PHOTOGRAPHER'S NOTE

Photography is the medium that best expresses my observations, documents my travel experiences, and helps me to satisfy my curiosity about the world, whether it is down the street or 'Down Under'. Carrying a camera gives me a license to explore new places and a self-confidence to engage with strangers in their work settings and in their daily lives.

I've spent a good part of my life sharing the resulting images in exhibitions, on the pages of books, in magazines and newspapers. A photograph is meant to be shared. It needs to be seen. Yet not everyone sees the same things in a photograph, or sees them in the same light. We see what we want to see; we make our own interpretations; and we discover new details when we look again at the image. Remember the film 'Blowup'?

A photograph is like a joke. Some people laugh their heads off. Others just smile. Some don’t get it.

I can barely explain what makes me take a photograph of something. It is a reflex action, a magical surge of recognition between my brain and my eye connecting with my finger on the shutter button. Seeing the printed image from the negative reminds me of what I saw – the humor of the situation, or the poignancy, the play of shadows, the graphic patterns, the composition; the juxtaposition of elements.

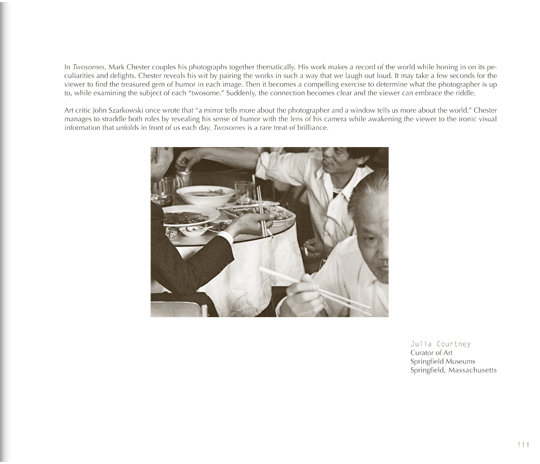

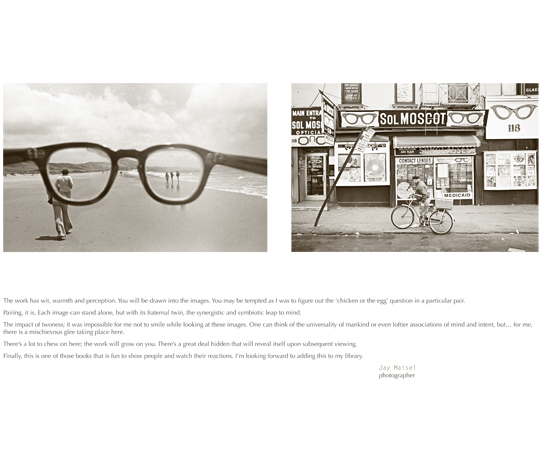

'Twosomes' is a compilation of “twosomes and then some.”

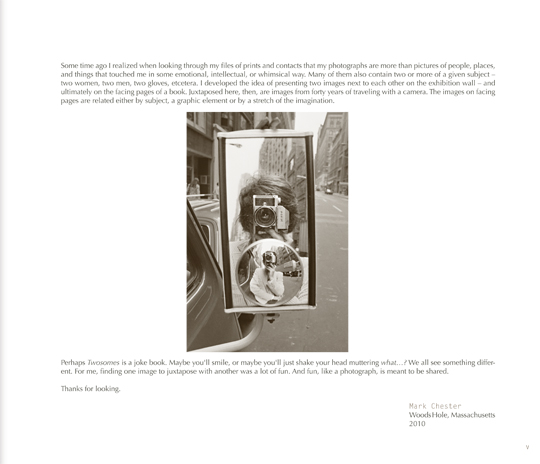

Some time ago I realized when looking through my files of prints and contacts that my photographs are more than pictures of people, places, and things that touched me in some emotional, intellectual, or whimsical way. Many of them also contain two or more of a given subject – two women, two men, two gloves, etcetera. I developed the idea of presenting two images next to each other on the exhibition wall – and ultimately on the facing pages of a book. Juxtaposed here, then, are images from forty years of traveling with a camera. The images on facing pages are related either by subject, a graphic element or by a stretch of the imagination.

Perhaps Twosomes is a joke book. Maybe you'll smile, or maybe you'll just shake your head muttering what…? We all see something different. For me, finding one image to juxtapose with another was a lot of fun. And fun, like a photograph, is meant to be shared.

Thanks for looking.

Mark Chester

Woods Hole, Massachusetts

2010

PHOTOGRAPHER'S NOTE

This is not a picture book, but rather one that gives us a certain picture of America, from California, across the Rockies and Great Plains, along the Atlantic and through New England. These photographs cover a time span of 25 years.

NO signs are everywhere. There's no escaping them. They lurk at us from walls, windows, doors, buildings, fences, trucks, roads, and even trees. They are at train stations, bus depots, and airports. Wherever we travel, a NO sign lingers about — in cold bold, striking red, in scrawled letters or fancy script. They are "signs of the times," an anthropological-sociological measure of America; they are words penned by pundits, poets, philosophers, and would-be comics.

But there's something more to their literal meaning than meets the eye. For embedded in the metal, wood, plastic, or cardboard message, there is a soul — a subtle hint of a personality who made the sign. In effect, these signs reflect human character.

I wonder who that person is behind the sign. I conjure up an image of an individual telling us SORRY, NO FREE MATCHES. He's a grouch; a rumpled-looking fellow always frowning. Wheras the creator of NO DOGS, VICIOUS GARDENER is an urbane, smiling Ivy Leaguer with a second home in the country.

I never did meet the person who made NO DANCEING (sic). I was a high school student in the '60s when I saw this sign. It made me aware of the existence of "No" in America.

I didn't take photographs back then. So I took the sign instead. I don't know why. The sign was hanging above an old juke box in a pizza shop.

How NO DANCEING remained in my possession for so long is amazing. It's really a fortuitous sign because it germinated the idea for this book five years ago when I rediscovered it in a carton of old papers.

Since then, I have photographed more than 300 NO signs in various parts of the country. They are an eclectic bunch: misspelled, graphically ugly, some barely readable with letters faded by the weather. Others are funny and cute. Some have drawings. A few are downtrodden. Most are upbeat.

I saw these signs inadvertently while walking or driving. Often I felt as though a magnet were pulling me into a situation or place where, to my surprise, a NO sign was hanging. For example, the time I made a wrong turn down a country road near Poughkeepsie, New York, and found NO PERMANENT PLANTINGS wired to a cemetary gate. Or the day I was in Ephrata, Pennsylvania, and walked into a public restroom that warned in large letters NO LOAFING. Then there was the truck-stop cafe near Reno, Nevada, off Interstate 80, where a sign attached to the food cart told patrons NO DOGGIE BAGS FOR BUFFET.

I am basically a people photographer. I like to shoot subjects that move and human conditions that are moving. At the outset, this book posed a challenge. How to photograph words and make them visually exciting? While there was the slight technical problem of solving glare — many signs were behind glass doors or windows — there was also the problem of dealing with some unwilling people who wouldn't allow me to photograph their NO sign. How absurd it seemed! Here they displayed their sign in the open public, yet refused having it recorded on film. After a while, sensing who might be "paranoid," I didn't ask permission, and just shot the picture anyway, figuring that had I asked, I'd have been turned down.

In retail stores when I sensed this "being-refused-if-asked," I had a tactic. I bought something, then took my photographs while the clerk rang up the sale.

Generally though, people were cooperative and I didn't have to play games. They were friendly and amused about the book idea. Some even gave me leads for other NO signs nearby.

Most of these signs were shot with a wide-angle lens, either a 20mm, 28mm or a 35mm. Occasionally, I used a 55mm macro (close-up) or a 105mm telephoto. When possible, I juxtaposed the sign with candids of people. Also, I incorporated other elements into the frame to establish a point of reference and to make the photograph graphically interesting.

Though some of the signs are a conscious attempt to be humorous, most of them are just plain funny without trying to be. Nor is there any deeper, underlying message than what they already spell out.

This book is merely a collection of seriously-silly photographs in which I took delight in discovering a positive side of no. Cha, cha, cha.

Mark Chester, San Francisco, 1986

DATELINE AMERICA

Charles Kuralt received three Peabody Awards, two of these Personal Awards, and ten Emmy Awards, and wrote several books including To The Top of the World, Dateline America, On The Road With Charles Kuralt, Southerners, North Carolina Is My Home, and A Life On The Road.

In 1981, he received the George Polk Memorial Award for national television reporting, and was named Broadcaster of the Year in 1985 by the International Radio-Television Society.

As a Peabody winner, it was said that Charles Kuralt "discovered that individualism still flourishes and the pioneer spirit lives on" — in the United States in 1975 — attention was called to his "rare skills in research and his sympathetic character delineations" and to his "nostalgic vignettes" in the 1960s in "the midst of daily crises."

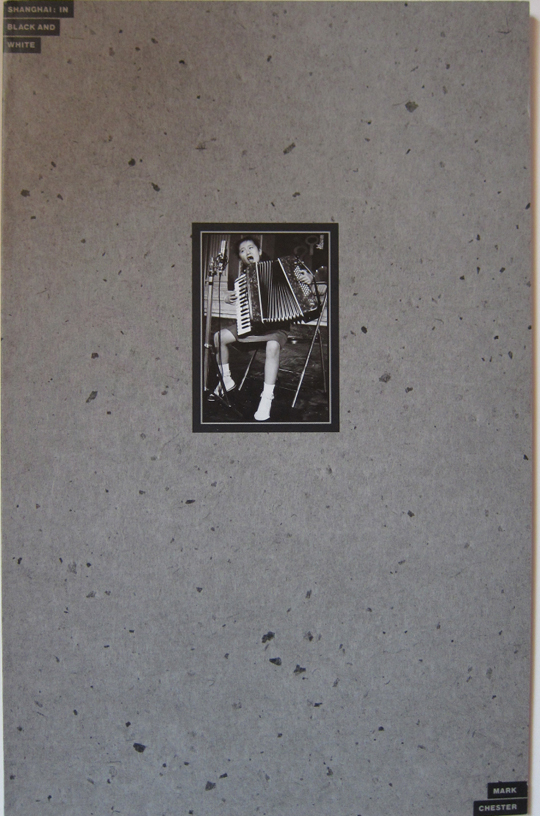

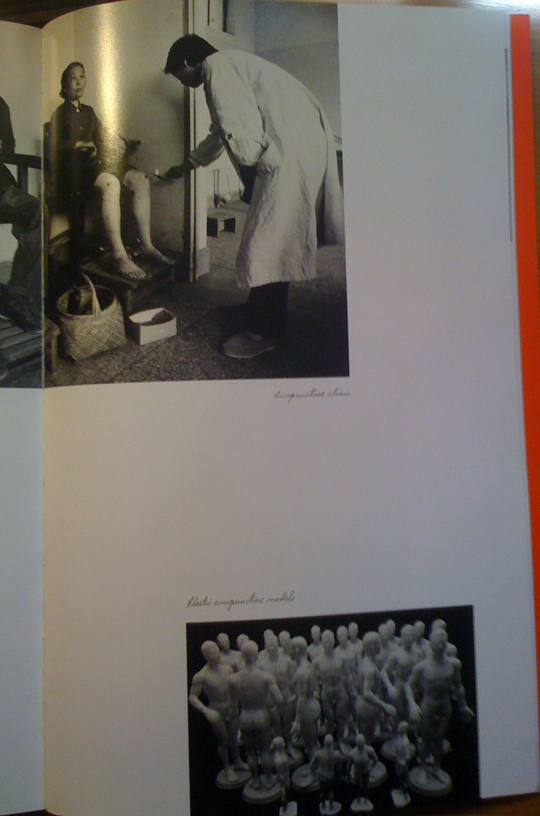

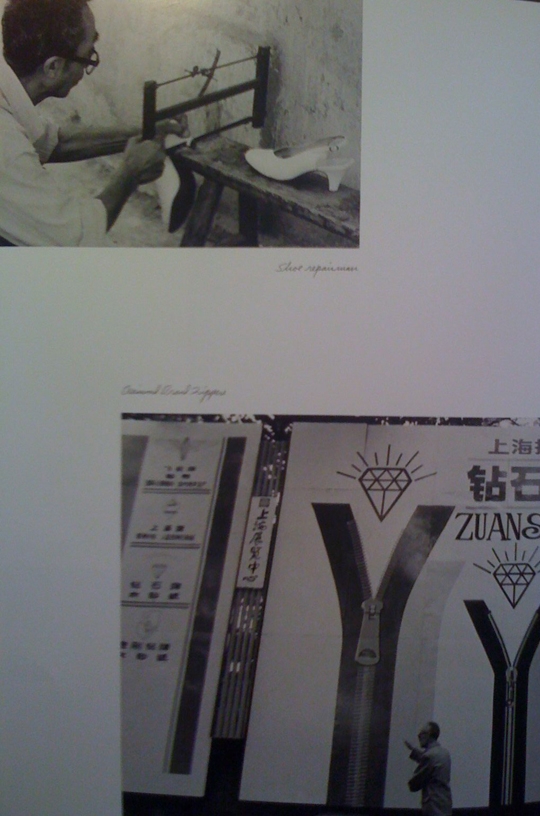

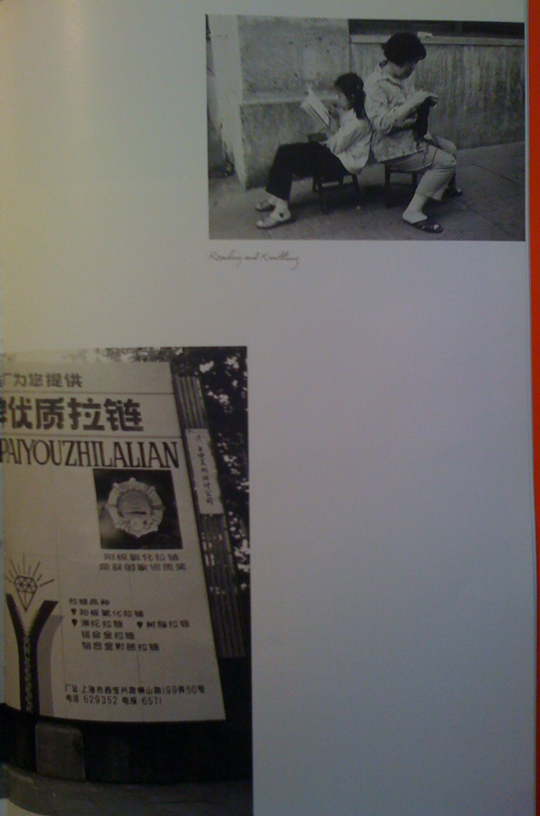

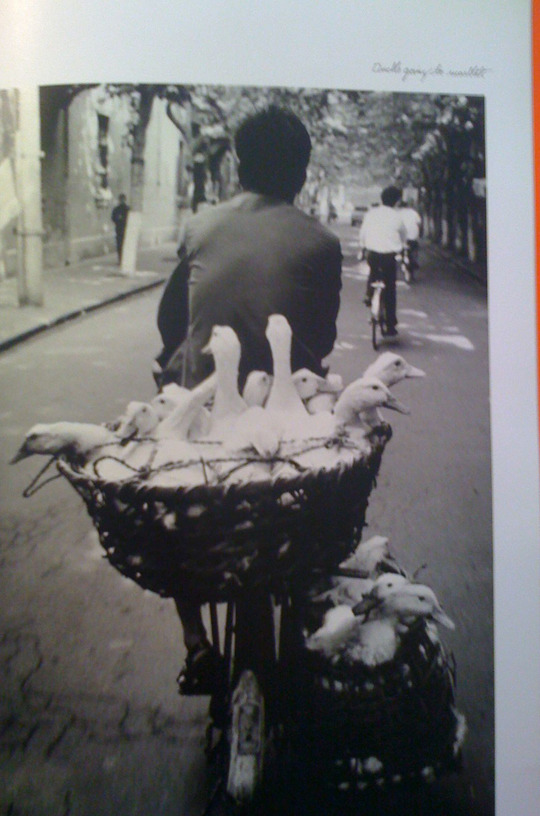

Shanghai: In Black and White

PHOTOGRAPHER'S NOTE

It was a good sign.

The board by the hotel desk spelled it out: "May 22 ... Thursday ... Weather: Fine." My first day in China, ever, was going to be fine. I hurried eagerly through the lobby and on outside to the sounds of Shanghai. Dawn was barely breaking, but streets were already teeming. Joining ranks with pedestrians and bicycle riders, I was soon swept into the rhythm of the city.

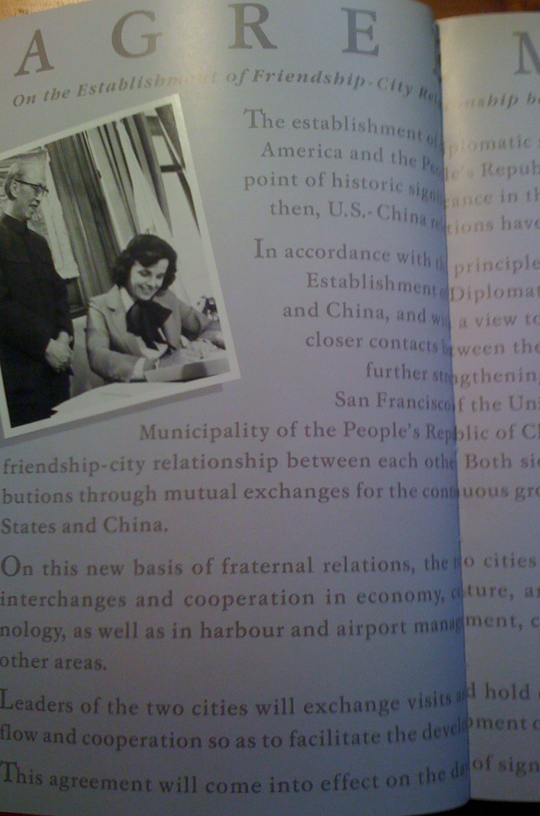

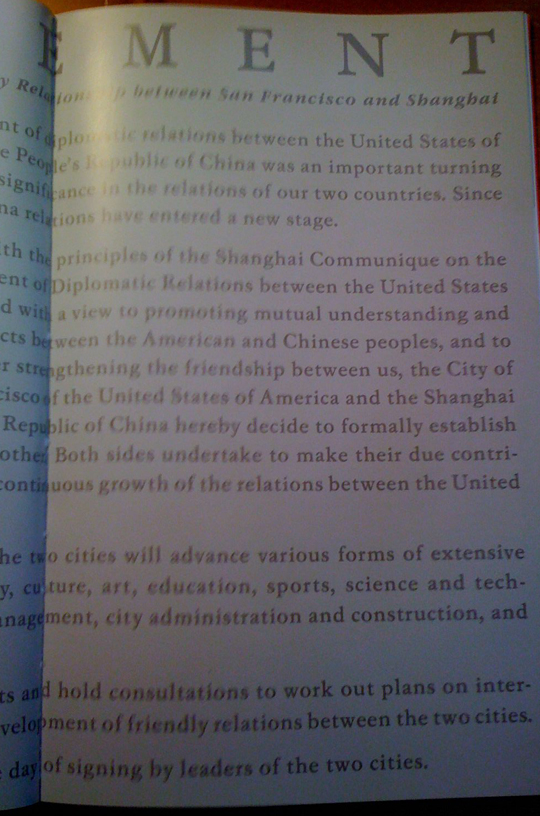

I went to Shanghai specifically to photograph the people and document their lifestyle as a self-assigned project. The idea came to mind seven years ago when I covered the Friendship City Agreement signing between Mayor Dianne Feinstein and Shanghai Vice-Mayor Zhao Xingzhi. From the outset, each stage of the project has been like a piece of a puzzle falling into place.

First, the San Francisco/Shanghai Friendship Committee accepted my proposal as part of its ongoing cultural exchange program; then the People's Government of the Municipality of Shanghai gave its approval; then the San Francisco Main Library allocated exhibition space. All of this set into motion a legitimate fundraising campaign for a non-profit community arts project.

I selected the Main Library as an appropriate viewing space because it offers educational opportunity to everyone. These photographs of our sister-city are for everyone. They teach us something about life in Shanghai in relation to our own.

It was no small task taking photos in Shanghai. The city is overwhelming. To help ease the intensity of this project and draw closer to the culture, I brought along Pei-Wei (Bill) Cheng, as translator, assistant, diplomat, advisor and friend. Chang is Shanghainese and professor of journalism and mass communication at Fudan University. He is currently on sabbatical. Bill, 65, is also Honorary Vice-President of the China Photographers' Association, Shanghai Branch. Besides knowing the local patois, people in all places and the lay of the land, he understands how a photographer thinks and sees, an understanding that proved valuable.

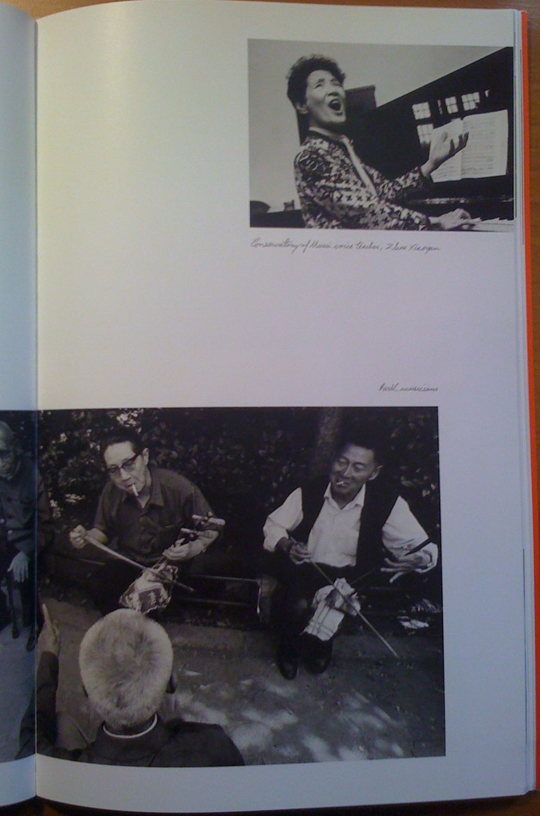

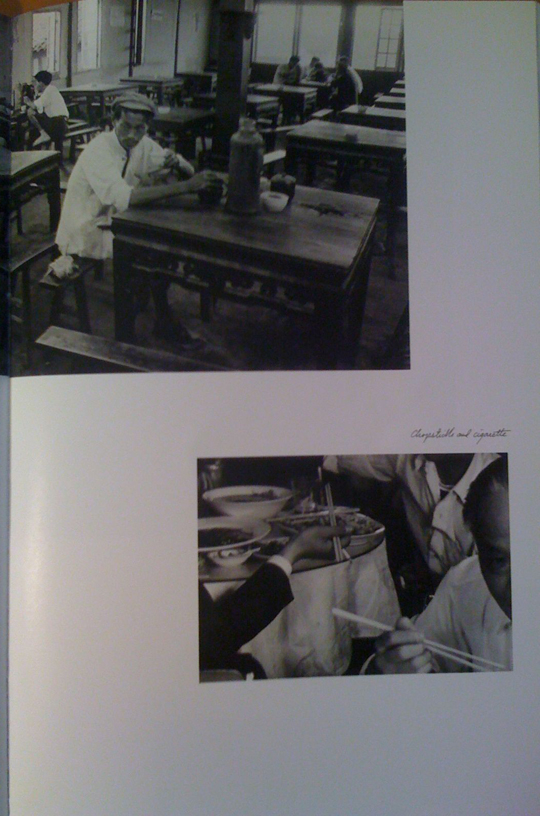

At our first meeting with the Division Chief of the Foreign Affairs Office and his staff, Bill conveyed my modus operandi and suggested a list of categories to explore—arts, culture, music, industry, education, religion, sports, among other general topics.

It was a memorable meeting. We sat in a huge reception room on couches that had white doilies draped on the backs and straddling the armrests. At first it was formal and stiff. The Division Chief spoke softly. His English was very good. We sipped tea, chit-chatted, smiled and joked. But we were also trying to figure eachother out, wondering what we have in common, how are we different. The silent pauses only magnified the awkwardness between us. We sipped more tea and philosophized. But in time we loosened up, and by the end of our talk, we are no longer strangers.

A general plan was initiated that allowed flexibility, though it was necessary to have a logistical schedule for each week. Arrangements with factories, institutions and individuals had to be made in advance , either by telephone, mail, and in some circumstances, by messenger.

While I only had six weeks to photograph the mundane, offbeat and the high level, I learned to be patient when the schedule didn't go as planned. I was anxious during my stay, and sometimes frustrated at missing a good picture here and there. I worried that I might not get enough good images to show. But I also believed that I was in the hands of fate, and that wherever I happened to be at any moment, I was at the right place.

For example, at the Children's Palace, I was shooting youngsters playing their instruments. I was about to leave when a little girl came to the microphone carrying her accordion. There was a certain captivating look about her, so I stayed. And when she began to sing, I noticed that her two front teeth were missing. I waited patiently for the right moment, the right expression on her face.

When not scheduled to visit any particular place, I roamed the city and rode the buses, either alone or with Bill. At the end of the day I was tired, saturated with the images in my head, praying they were on my film, too. Forty days, the length of my stay, is a short time to capture the pulse of a city like Shanghai.

This selection of photographs is edited from nearly 12,000 frames. It was a difficult choice as Shanghai is a colorful city, especially in black and white.

May 1987

Mark Chester

San Francisco